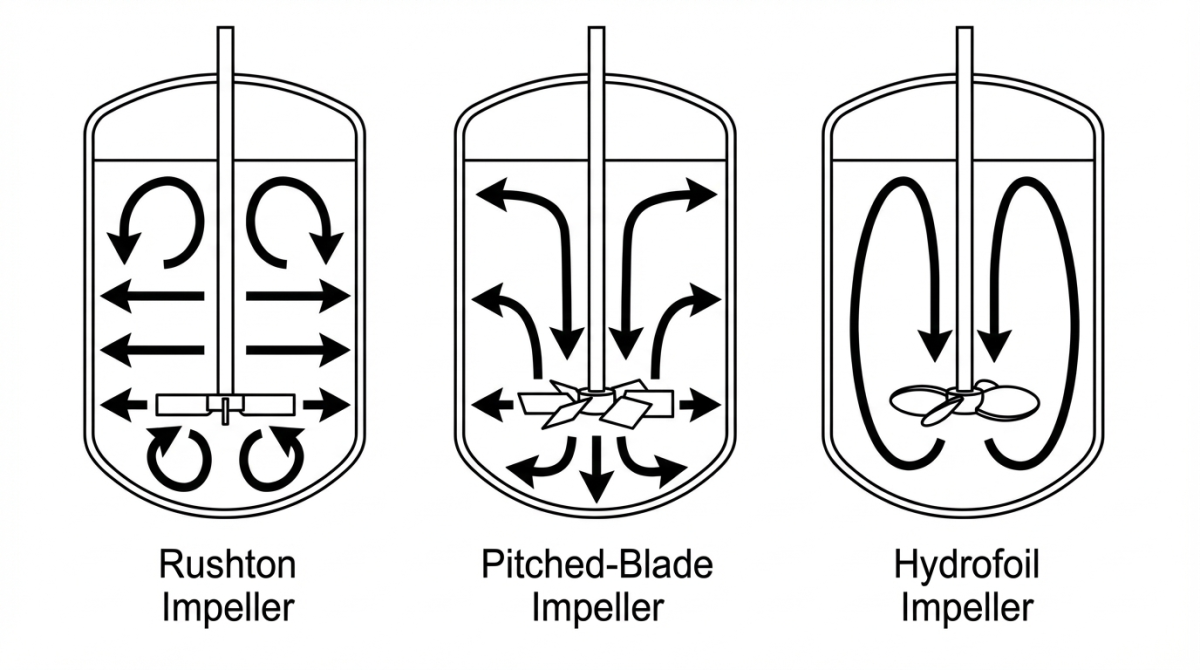

Flow patterns in stirred-tank bioreactors: Rushton, pitched-blade and hydrofoil

In a stirred-tank bioreactor, the flow pattern is largely set by the impeller design. Three of the most common options are the Rushton turbine, the pitched-blade impeller and the hydrofoil impeller.

Each one drives the fluid in a different way. A Rushton pushes the liquid mainly sideways (radial flow), pitched-blade designs combine axial and radial components, and hydrofoils pump primarily in the axial direction. Those differences in flow direction directly affect mixing, bubble dispersion and the local shear environment.

Rushton impeller: Radial flow and high shear

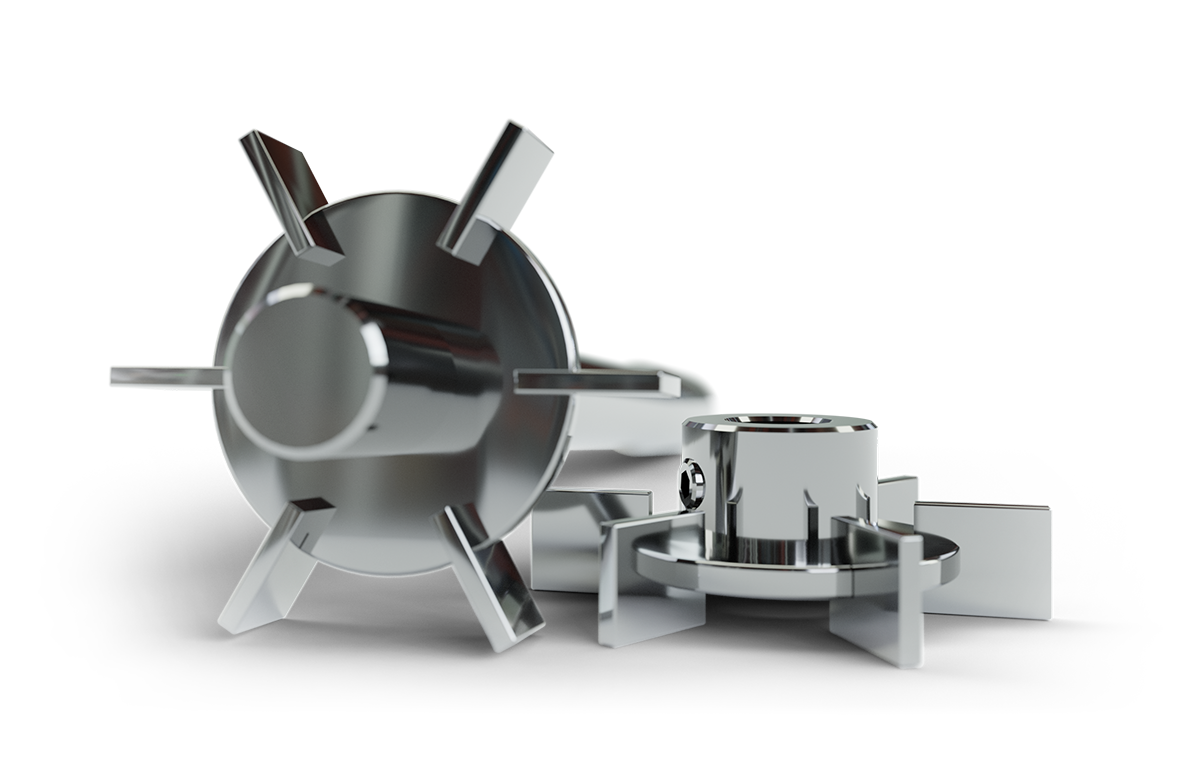

The Rushton turbine is a flat disk fitted with 4–6 vertical blades. It generates a predominantly radial flow pattern, meaning the liquid is pushed outward towards the vessel wall. When that radial jet hits the wall (and the baffles), it splits into two recirculation loops, one above and one below the impeller plane.

Because the blades are flat, a Rushton creates high local shear, with strong velocity gradients close to each blade. It is also very effective at breaking up gas bubbles, which greatly increases gas–liquid interfacial area. The result is typically very high kLa and excellent oxygen transfer, although this comes with higher power demand..

Key characteristics of a Rushton turbine:

- Radial flow: The discharge is directed sideways toward the vessel wall.

- High shear: Flat blades generate strong local turbulence.

- Very high oxygen transfer (kLa): Efficient bubble breakup often delivers the highest kLa values.

- Typical use: Aerobic microbial fermentations (e.g., E. coli, yeasts) where organisms tolerate shear and oxygen transfer is prioritised over cell fragility.

Pitched-blade impeller: Mixed axial–radial flow

The pitched-blade impeller consists of 4–6 flat blades set at an angle of around 45° to the shaft. This geometry generates a mixed axial–radial flow. Part of the liquid is driven upward or downward along the vessel axis, while another fraction is pushed outward in the radial direction. The axial component promotes vertical circulation, whereas the radial component adds lateral recirculation. In practice, this produces a balanced flow pattern that mixes the medium efficiently without excessive turbulence.

Key characteristics of a pitched-blade impeller:

- Mixed flow pattern: Combines axial and radial flow, helping to reduce dead zones inside the reactor.

- Moderate shear: Lower than a Rushton turbine, as the axial flow component softens the mechanical stress on cells.

- Good oxygen transfer: Provides effective gas dispersion, although kLa is typically somewhat lower than that of a Rushton turbine at the same power input.

- Typical use: Well suited for shear-sensitive cell cultures (CHO, HEK, mammalian or insect cells) that need efficient mixing without excessive shear. It is also used in moderate microbial processes and in liquid–liquid mixing applications.

Hydrofoil impeller: Axial flow and low shear mixing

The hydrofoil impeller (also referred to as a hydrodynamic impeller) typically features 3 to 4 curved blades with an aerodynamic profile. Its design is optimised to generate a predominantly axial flow, most often in a down-pumping configuration. This promotes very efficient vertical recirculation of the liquid while requiring relatively little energy. Thanks to the curved blade geometry, hydrofoil impellers generate minimal shear compared with other designs. Even at low rotational speeds, they can move large fluid volumes, which helps preserve the viability of delicate cell cultures.

Key characteristics of a hydrofoil impeller:

- Strong axial flow: efficiently pumps the liquid vertically (upward and downward circulation).

- Very low shear: minimises local shear forces, making it well suited for sensitive cultures.

- High energy efficiency: characterised by a low power number (Po), high pumping capacity and low energy consumption.

- Oxygen transfer: although the absolute kLa may be lower than that of a Rushton turbine, the high circulation rate maintains effective oxygenation.

- Typical use: recommended for very delicate cell cultures or moderate- to high-viscosity media (up to tens of thousands of cP), commonly used in single-use bioreactors and in gentle scale-up strategies where mechanical stress must be minimised.

Comparison of bioreactor flow patterns and performance

The differences between these impellers can be summarised as follows. Flow direction is the first key distinction: the Rushton turbine generates a predominantly radial flow (directed towards the vessel walls), the pitched-blade impeller produces a mixed axial–radial flow, and the hydrofoil drives the liquid mainly in an axial (vertical) direction. As a result, the level of induced shear also varies, being highest with Rushton turbines, intermediate with pitched-blade impellers, and lowest with hydrofoil designs.

There are also clear differences in oxygen transfer performance. Rushton turbines are very effective at breaking gas bubbles, leading to very high kLa values. Axial-flow impellers typically achieve slightly lower kLa at the same power input, but they compensate through strong bulk circulation, which helps maintain effective oxygenation. In terms of energy consumption, Rushton turbines require the most power (Po ≈ 5–6), pitched-blade impellers fall in an intermediate range (Po ≈ 2–3), and hydrofoils are the most efficient option (Po ≈ 1–1.2).

Overall, axial impellers (pitched-blade and hydrofoil) provide gentler and more energy-efficient mixing per unit volume, while the Rushton turbine delivers maximum gas dispersion and oxygen transfer when high shear and power input are acceptable.

Shear, mixing and oxygen transfer in bioreactor flow patterns

In general terms, axial-flow impellers, such as pitched-blade and hydrofoil designs, achieve more effective bulk mixing than radial impellers. This results in faster homogenisation at the same power input and a reduction of zones with extreme local shear. In contrast, the Rushton turbine generates strong, highly localised turbulence that favours gas dispersion rather than overall circulation. Most experimental and CFD studies agree that axial impellers outperform radial ones in terms of mixing intensity and volume turnover.

With respect to dissolved oxygen, Rushton turbines typically deliver the highest kLa values due to their aggressive bubble breakup. Axial impellers generally reach slightly lower kLa at equivalent power, but they can compensate through improved fluid circulation and more uniform gas distribution. In practice, at similar power inputs, the Rushton turbine often has an advantage in absolute kLa, while hydrofoil impellers achieve effective oxygenation with lower energy consumption by maintaining high recirculation rates throughout the vessel.

Cell suspension and recommended application

The choice of impeller also depends strongly on the type of culture being processed. Robust microbial organisms, such as E. coli and yeasts, tolerate high shear levels well, which is why Rushton turbines are commonly used to maximise oxygen transfer in these systems. In contrast, more sensitive cultures, including mammalian and insect cells, require gentler mixing conditions. In these cases, axial-flow impellers are generally the preferred option, as they provide effective circulation while limiting local shear.

For example, CHO and HEK cells typically show better growth and viability with pitched-blade or hydrofoil impellers, since these designs reduce turbulence and mechanical stress. In viscous media or large-scale reactors, hydrofoil impellers are particularly advantageous. Their geometry allows them to handle fluids with high viscosity (up to approximately 50,000 cP) while delivering high circulation rates with minimal power input. In more complex or hybrid processes, it is also common to combine impeller types, such as placing a pitched-blade impeller above a Rushton turbine, to balance mixing efficiency and oxygen transfer according to process needs.

Table: Flow pattern comparison of common bioreactor impellers

| Feature | Rushton (radial turbine) | Pitched-blade (PBT) | Hydrofoil |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow pattern (dominant) | Radial (strong horizontal jet) | Mixed axial–radial (diagonal discharge) | Axial (strong vertical pumping) |

| Main circulation in baffled STR | Two toroidal loops (above and below the impeller) | Large loop; depends on down- vs up-pumping | Clean vertical loop; depends on down- vs up-pumping |

| Best at | Bubble breakup and gas dispersion | Versatile bulk mixing | Efficient bulk circulation with low power |

| Shear near blades | High | Moderate | Low |

| Gas dispersion / kLa (typical) | Very high | Good (often lower than Rushton at same power) | Good relative to power input (efficient) |

| Energy efficiency (Po trend) | Low (Po ~5–6) | Medium (Po ~2–3) | High (Po ~1–1.2) |

| Typical use cases | Aerobic microbial fermentations (high O₂ demand) | Cell culture and general-purpose mixing | Shear-sensitive cultures, gentle scale-up, viscous media |

Choosing the right flow pattern for your bioreactor

In a stirred-tank bioreactor (STR), the flow pattern is a key process variable that directly determines how the tank is mixed, how gas is dispersed, the achievable kLa, and, most importantly, the level of shear to which the culture is exposed.

If you want to go deeper into impeller selection beyond fluid motion alone, we recommend the other article in this series, which compares Rushton, pitched-blade and hydrofoil impellers from the perspective of kLa, energy consumption, shear and scale-up criteria. That approach helps support decisions based on data rather than simple rules of thumb.

Within this context, TECNIC offers both single-use and multi-use stainless steel bioreactors that can be configured with Rushton and pitched-blade impellers. This flexibility allows the agitation system to be adapted to the specific process type (microbial or cell culture) and to the chosen scale-up strategy. If you need to validate which flow pattern and impeller configuration best fit your culture, our team can support you in defining the most appropriate geometry and agitation setup for your application.

Frequently asked questions about flow patterns in stirred-tank bioreactors

In an STR, the flow pattern is the dominant circulation path created by the impeller inside the vessel. It describes how liquid moves (axial, radial or mixed), which directly affects mixing time, gas dispersion, local shear and how quickly the whole tank becomes homogeneous.

Radial flow pushes liquid sideways toward the tank wall (strong horizontal jet). Axial flow pumps liquid mainly up or down along the vessel axis (strong vertical circulation). Mixed flow combines both components, typically with a diagonal discharge that improves bulk circulation while maintaining some radial mixing.

A Rushton turbine is predominantly radial-flow. It generates a strong horizontal jet that hits the vessel wall and splits into two circulation loops (one above and one below the impeller), especially in baffled tanks. This pattern is typically associated with strong gas dispersion and high local turbulence.

A pitched-blade turbine produces mixed axial–radial flow. The discharge leaves the blades diagonally, so the impeller can pump up or down (depending on blade orientation), while still generating a radial component that helps distribute flow across the vessel diameter.

Hydrofoil impellers are mainly axial-flow designs. They are optimised to move large liquid volumes vertically (strong pumping) with relatively low power input, typically creating a clean vertical circulation loop that supports efficient bulk mixing at lower local shear.

Baffles (typically 3–4 vertical plates) reduce swirl and suppress vortex formation, so more of the impeller power is converted into a defined flow pattern (axial, radial or mixed) instead of “spinning” the whole liquid volume. In baffled STRs, circulation loops become more stable, mixing time usually improves, and gas dispersion tends to be more consistent. Without baffles, strong tangential motion can dominate, leading to poor top-to-bottom exchange, surface vortexing and less predictable oxygen transfer.

Yes. Blade orientation determines whether the impeller pumps liquid downward or upward, which changes where high-velocity zones form and how quickly the top and bottom of the tank exchange fluid. Down-pumping is often preferred for surface-to-bottom circulation and gas handling, while up-pumping can be useful in specific suspension or surface renewal scenarios.

Axial and mixed-flow impellers typically improve top-to-bottom circulation and reduce stagnant regions, especially in taller tanks. Radial turbines can mix efficiently near the impeller zone but may require multiple impellers or specific placement to avoid stratification in large volumes.

Gas dispersion depends on how the impeller interacts with bubbles and where gas is carried in the vessel. Radial turbines often break bubbles efficiently and can deliver high kLa at higher power. Axial designs can maintain effective oxygenation by sustaining strong circulation and distributing bubbles throughout the working volume, depending on sparger and gas rate.

Multiple impellers are common in tall vessels, higher viscosity media or large-scale STRs where one impeller cannot circulate the entire height effectively. Adding a second (or third) impeller helps stabilise axial circulation, reduce stratification and improve overall gas and nutrient distribution across the full liquid column.

References

- Fluid Flow and Mixing With Bioreactor Scale-Up – Bioprocess International. Explains how impellers generate axial and radial circulation patterns and how these affect mixing and mass transfer during scale-up.

- A Review of Stirred Tank Dynamics: Power Consumption, Mixing Time and Impeller Geometry – ResearchGate. Technical review covering stirred-tank hydrodynamics, flow patterns and the impact of impeller geometry on mixing performance.

- Stirred-Tank Bioreactors – ScienceDirect Topics. Engineering overview of flow behaviour and mixing patterns in stirred-tank bioreactors.

This article provides a technical, data-driven analysis of bioreactor impellers, comparing Rushton, pitched-blade and hydrofoil designs from the perspective of flow patterns, oxygen transfer (kLa), shear environment and energy efficiency across laboratory, pilot and production-scale stirred-tank bioreactors. The content is structured to help readers understand how impeller-driven flow influences mixing behaviour and how these differences impact process performance and scale-up decisions.

This article has been reviewed and published by TECNIC Bioprocess Solutions, a manufacturer of scalable stirred-tank bioreactors, tangential flow filtration systems and single-use consumables for bioprocess development, pilot operation and GMP manufacturing.