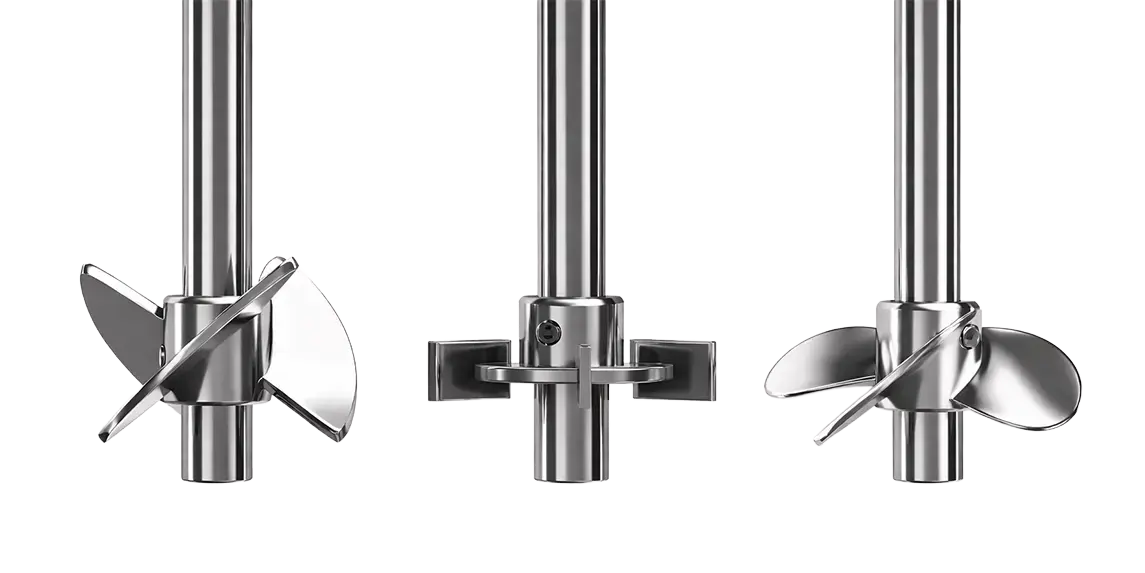

Bioreactor impeller comparison: Rushton, pitched-blade and hydrofoil

Impellers are key components in bioreactors, responsible for homogenising the culture medium and promoting dissolved oxygen transfer. Their design has a direct impact on mixing efficiency, nutrient and oxygen distribution, and the shear forces experienced by cells, making impeller selection a critical upstream process decision.

Key takeaways

Mixing performance: Impellers ensure homogeneous conditions inside the bioreactor, preventing concentration and temperature gradients that can affect cell growth and product quality.

Oxygen transfer (kLa): Gas dispersion and bubble breakup depend strongly on impeller geometry, directly influencing the achievable oxygen transfer rate.

Shear environment: Different impeller designs generate distinct shear profiles, which can be beneficial for robust microorganisms or harmful to shear-sensitive cell cultures.

Suspension capability: Proper impeller selection keeps cells and solids uniformly suspended, avoiding sedimentation or localised high-density zones.

Process scalability: Impeller type and configuration play a central role in transferring processes from lab to pilot and production scale.

In practice, impellers enable efficient mixing and controlled oxygen supply to the culture. For example, a six-blade Rushton impeller is commonly used in microbial fermentations with shear-tolerant organisms, as it supports high agitation speeds and delivers high oxygen transfer capacity.

Types of bioreactor impellers

A variety of impeller designs are used in bioreactors; here we focus on the most common ones: the Rushton turbine, the pitched-blade impeller, and the hydrofoil impeller.

Rushton turbine (radial, flat blades)

The Rushton turbine consists of a disk with 4–6 straight blades mounted perpendicular to the shaft. Its flow pattern is mainly radial: the liquid is driven from the centre of the impeller towards the vessel walls. This design results in:

- High shear: The flat blades break gas bubbles and generate intense local shear, promoting high energy dissipation.

- Efficient gas dispersion: By breaking bubbles, the interfacial area increases and, consequently, oxygen transfer (kLa) can reach very high values, albeit at the expense of higher power consumption.

- Efficient mixing under turbulent conditions, keeping light solids in suspension.

It is particularly well suited for aerobic microbial fermentations (for example, E. coli), where high oxygen transfer rates are required and the cells tolerate shear well. It is also widely used in systems with multiple impellers mounted along the shaft at industrial scale, as its geometry is well characterised and scales reliably.

However, its strong radial flow does not promote downward axial recirculation and therefore does not entrain additional air from the liquid surface, which can be advantageous when unwanted surface aeration needs to be avoided.

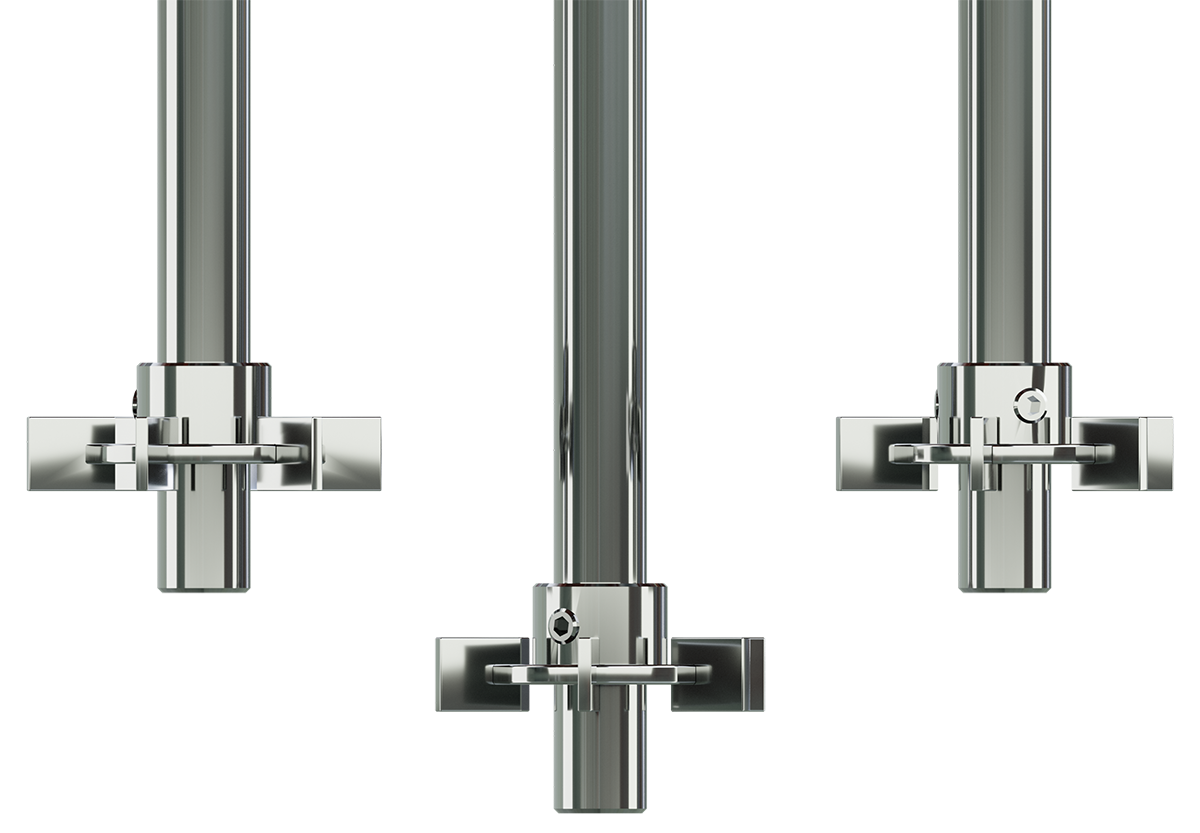

Pitched-blade impeller

The pitched-blade impeller (or pitched-blade turbine, PBT) typically features 4–6 flat blades inclined at approximately 45°. This design generates a mixed axial–radial flow: part of the liquid is driven upward or downward (axial component), while another part is directed radially towards the vessel walls. The inclined blades result in:

- Moderate shear: Lower than that generated by a Rushton turbine, as the axial flow component softens the agitation.

- Efficient mass transfer: It provides good gas dispersion, although the resulting kLa is typically lower than that of a Rushton turbine at the same power input.

- Versatile mixing: Suitable for both aerated and non-aerated systems, maintaining a homogeneous suspension. It is widely used in mammalian cell cultures (for example, CHO or Vero cell lines), where reduced shear helps preserve cell viability.

In practice, a pitched-blade agitator produces a combination of axial and radial circulation. It is very effective at homogenising liquids containing suspended solids and at dispersing oxygen bubbles. In bioprocess design, it is often operated in a down-pumping configuration to promote recirculation, or in an up-pumping configuration to minimise foam accumulation.

Hydrofoil impeller

The hydrofoil impeller, also known as a marine-type impeller, features three aerodynamically curved blades (with an airfoil-like profile) inclined at approximately 45°. Its flow pattern is predominantly axial, particularly in the downward direction. Key characteristics include:

- Low shear: Thanks to its curved blade profile and operation at lower rotational speeds per unit volume, it generates reduced shear forces, making it suitable for shear-sensitive cells.

- High axial pumping efficiency: It maximises vertical flow (pumping capacity) with relatively low mechanical effort.

- Lower energy consumption: It has a low power number and provides excellent pumping performance with low energy dissipation.

- Moderate mass transfer: It can achieve adequate kLa values by promoting uniform circulation, although it typically requires fine gas dispersion to optimise oxygen transfer.

Due to its high efficiency and reduced mechanical stress, hydrofoil impellers are well suited for large-scale cell culture applications and for reactors with a high height-to-diameter ratio, where strong vertical circulation with minimal velocity gradients is required. In summary, they provide rapid upward and downward flow, enabling effective mixing at low RPM, albeit with a more complex design.

Performance comparison: kLa, shear and energy consumption

The three impeller designs differ significantly in terms of oxygen transfer performance, shear levels and power requirements:

Table: bioreactor impeller comparison (Rushton vs pitched-blade vs hydrofoil)

| Characteristic | Rushton (radial turbine) | Pitched-blade impeller | Hydrofoil (3 curved blades) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow pattern | Predominantly radial | Mixed axial–radial | Predominantly axial |

| O2 transfer (kLa) | Very high (efficient bubble breakup) | Good (lower than Rushton) | Relatively good (high efficiency) |

| Shear intensity | High (turbulent) | Moderate (gentle mixing) | Low (partially laminar flow) |

| Energy efficiency | Low (high Po, high power consumption) | Intermediate (medium Po) | High (low Po, reduced power consumption) |

| Typical applications | Microbial fermentations (E. coli, yeasts), intensive aeration | Shear-sensitive cell cultures (CHO, HEK) and liquid–liquid mixing | Large-scale cell culture, viscous fluids |

| Scale of use | Laboratory to industrial (typical in SS) | Laboratory to pilot (SU or SS) | Laboratory to industrial (SU or SS) |

| Typical materials | Stainless steel (SS 316L) | Stainless steel or polymers (SU) | Stainless steel or polymers (SU) |

Scale-up considerations (from laboratory to industrial production)

When scaling up a biotechnological process, it is critical to maintain or adjust agitation-related parameters in order to preserve the hydrodynamic behaviour of the system. The most common scale-up strategies include:

- Constant power per unit volume (P/V): Maintaining the same power input per unit volume helps ensure similar mixing conditions. However, as reactor size increases, the resulting increase in mixing time must be carefully controlled.

- Constant tip speed: Keeping the same linear velocity at the impeller tip helps protect cells, as mechanical stresses remain similar during scale-up. This approach often reduces mixing efficiency at large scale and may require an increase in impeller diameter.

- Constant mixing time: Ensures the desired level of homogeneity, but requires higher power input in large vessels.

- Constant kLa: Aims to maintain the same oxygen transfer capacity, which is particularly important for oxygen-sensitive mammalian cell cultures. In this case, higher energy input may be acceptable to reach the target kLa.

In practice, hybrid approaches are commonly applied. For example, a constant tip speed can be maintained while optimising reactor geometry (diameter-to-height ratio) and the arrangement of multiple impellers along the shaft.

The height-to-diameter ratio strongly influences the balance between axial and radial mixing. At larger scales, higher ratios are often preferred to promote axial circulation. In addition, industrial bioreactors frequently incorporate more than one impeller positioned at different heights to ensure uniform mixing in tall vessels.

Another key factor during scale-up is tip speed, which directly affects the mechanical stress experienced by the cells. For this reason, cell culture processes often aim to keep tip speed low during scale-up (e.g. < 1–2 m/s), whereas higher tip speeds are generally acceptable in microbial fermentations to enhance oxygen transfer.

In summary, successful scale-up requires adapting both bioreactor design and operating parameters (agitation speed, impeller configuration) to maintain homogeneous mixing, sufficient oxygen transfer and shear levels compatible with cell viability.

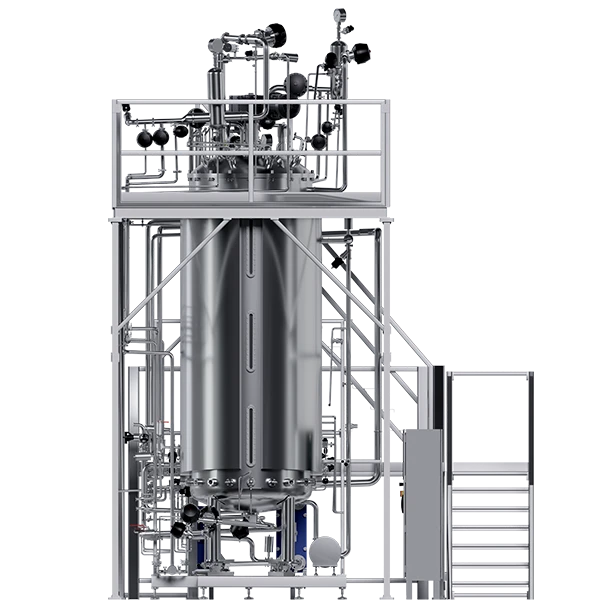

Stainless steel bioreactors vs. single-use bioreactors

In bioprocessing, both traditional stainless steel (SS) reactors and single-use systems are used. Each approach has specific implications for impeller selection and operation:

- Stainless steel bioreactors:

These are commonly used in industrial production. Their robust construction (SS 316L with sanitary surface finishes) allows intensive cleaning and repeated sterilisation through CIP/SIP. They are durable and can operate under a wide range of conditions, including high pressure and temperature. Impellers in SS systems are typically metallic (stainless steel) and can be cleaned and sterilised together with the reactor.- Advantages: High batch-to-batch reproducibility, controlled surface finishes (fewer product hold-up areas), and no concerns related to substances released from materials.

- Disadvantages: High initial investment and increased downtime due to cleaning operations.

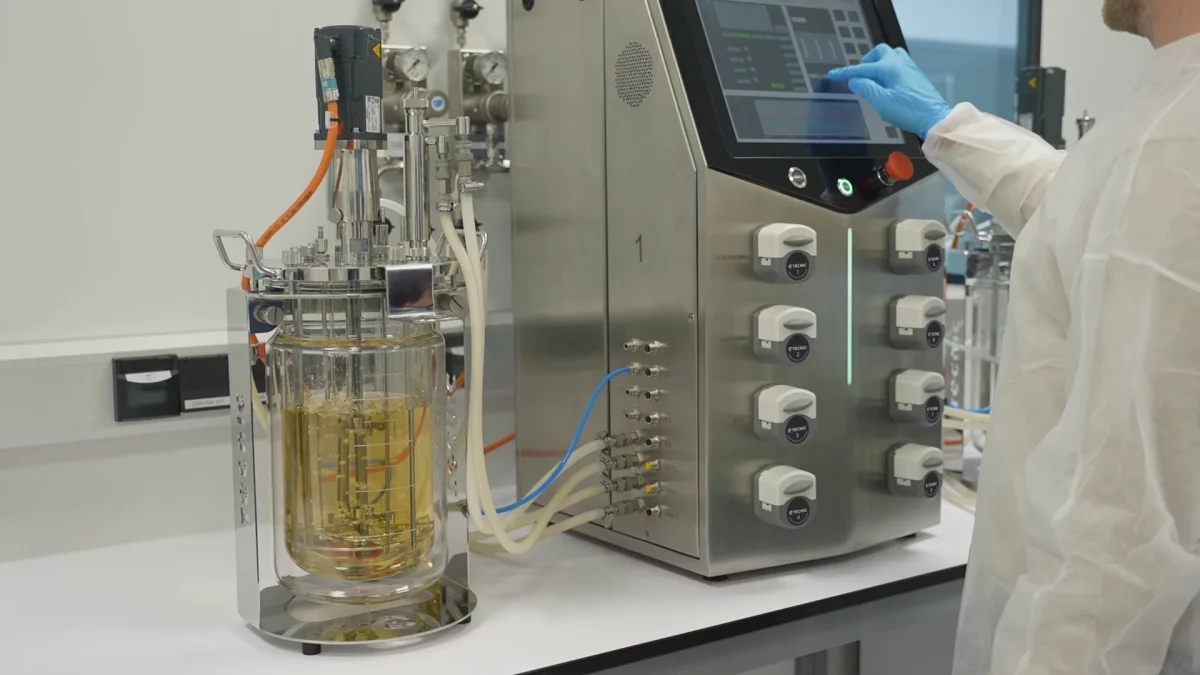

- Single-use bioreactors:

These systems use disposable polymer bags (PE, EVA, PVC, etc.) as the reaction vessel. They do not require in situ cleaning or sterilisation, as a new sterile assembly is installed for each batch. The impellers integrated into these systems are typically made of compatible plastics (such as polypropylene) and have designs similar to those used in stainless steel reactors.- Advantages: Elimination of cleaning and CIP time (greater flexibility for rapid development and multiproduct facilities), lower infrastructure investment (can reduce CAPEX), and ease of modular scale-up.

- Disadvantages: Limitations in operating temperature and sterilisation methods (not compatible with autoclaving), the need to evaluate potential release of substances from plastic materials into the product, and generally a more limited service life.

Cleaning, validation and compatible materials

The choice of impeller is also closely linked to the cleaning and validation requirements of the system. Key aspects include:

- Cleaning and sterilisation (CIP/SIP): In stainless steel bioreactors, clean-in-place (CIP) and steam-in-place (SIP) procedures are applied after each batch. Impeller design (blade angle, diameter) must allow proper access for CIP spray nozzles and avoid dead zones. For this reason, polished surface finishes (low roughness) are used on blades and sanitary seals. Typical materials include biopharmaceutical-grade SS 316L.

- Material validation and approval: Impeller components (blades, shafts, retainers) must comply with FDA and GMP requirements. For stainless steel systems, residual cleanliness and material biocompatibility are validated. In single-use systems, each bag and its impeller are supplied with material certifications (polymer type, adhesives and components), together with studies evaluating the potential release of substances from the materials into the culture medium. Suppliers typically provide documentation confirming compatibility with the process and with sterilisation methods such as gamma irradiation.

- Potential hold-up areas: Hygienic design aims to eliminate areas where product residues may accumulate. In single-use biobags, impellers are often moulded as a single piece to minimise crevices, and component connections are leak-tight. In stainless steel systems, welded joints are carefully designed and validated, and approved dynamic seals or PTFE rings are used to withstand aggressive CIP conditions (high pH).

- Verification systems: In stainless steel bioreactors, hydrostatic tests, SIP validation with tracers and detergent residue tests after CIP are commonly performed. In single-use systems, integrity tests (burst tests) and pressure leak tests are carried out prior to use.

In summary, impeller selection is closely linked to the cleaning and sterilisation strategy: metallic impellers in stainless steel systems must be compatible with repeated CIP/SIP cycles, whereas plastic impellers used in single-use systems are supplied pre-sterilised and discarded after use, eliminating the need for cleaning validation between batches.

Impeller selection based on process and development stage

The optimal choice of an impeller depends on the type of culture (microbial vs. cell culture), the scale, and the stage of process development. Some practical recommendations include:

- Cell cultures (mammalian cells, CHO, insect cells): Low shear conditions are prioritised. At laboratory and pilot scale (5–50 L), pitched-blade impellers or marine-type axial impellers are commonly used. For example, in a 50 L glass bioreactor for CHO cell culture, a 45° pitched-blade turbine operated in a down-pumping configuration at moderate speeds (~50–150 rpm) is typically selected to ensure uniform mixing without compromising cell viability. Single-use 50 L bags often incorporate an integrated pitched-blade or hydrofoil impeller.

- Microbial fermentation ( coli, yeasts): Higher shear levels are tolerated and high oxygen transfer is required. In small-scale reactors (5–10 L), a 4–6 blade Rushton turbine is typically used to maximise kLa. For instance, in a 5 L E. coli fermentation, a Rushton impeller is selected to provide efficient oxygen dispersion and maintain cells in suspension. In yeast cultures at around 100 L, Rushton turbines (during the growth phase) can be combined with an axial impeller positioned above to avoid surface air entrainment.

- Plant or photosynthetic cultures, or inoculum preparation: Pure axial-flow impellers (marine-type impellers) can be useful for delicate cultures that require homogeneous vertical circulation, although they are less common at small volumes.

- Development stages: During R&D phases, single-use bioreactors are often preferred due to lower investment requirements and the absence of cleaning steps, using versatile impellers (such as marine-type or hydrofoil designs) that can support multiple cell lines. At pilot and production scale, the selection depends on reactor size and process demands: large facilities typically rely on stainless steel systems with optimised (sometimes custom-designed) impellers, while modular or multiproduct facilities may continue to use scaled single-use platforms with the same impeller designs.

In practice, a common rule of thumb applies:

- For shear-sensitive cultures (cells), axial or pitched-blade impellers with low shear are preferred.

- For robust cultures (microorganisms), Rushton turbines with high gas dispersion capacity are typically selected.

As scale increases, it is also evaluated whether a transition from single-use to stainless steel systems is advantageous in order to facilitate validation and process control in large-scale production.

Practical examples of impeller selection

- CHO cell culture in a 50 L STR bioreactor: A 45° pitched-blade impeller (or a marine-type axial impeller) operated in a down-pumping configuration is recommended. This design provides mixed flow with reduced shear, making it suitable for maintaining mammalian cell viability. Operation at moderate agitation speeds (e.g. 70–120 rpm), depending on impeller diameter, ensures adequate oxygen transfer without compromising the cell line.

- E.coli fermentation in a 5 L fermenter: The classical choice is a six-blade flat Rushton turbine made of stainless steel. At high agitation speeds (e.g. 800–1000 rpm), this radial turbine delivers high oxygen transfer rates (high kLa) to meet bacterial oxygen demand, assuming E. coli tolerance to high shear. In a 5 L laboratory fermenter, a single Rushton turbine may be sufficient, although two impellers on the same shaft can be used if the reactor is relatively tall.

- Microbial fermentation (yeast) in a 100 L reactor: A dual or triple Rushton configuration with side baffles is commonly installed, as the well-established radial geometry of the Rushton turbine facilitates industrial scale-up. However, in tall reactor configurations, pitched-blade impellers may be added in the upper section to improve axial circulation.

- Cell culture process at development stage: At small volumes (1–10 L), a single-use bioreactor equipped with a hydrofoil impeller can be advantageous, providing high axial flow with minimal shear. For critical process phases, hydrofoil impellers manufactured from USP-certified materials may be selected to ensure compatibility with regulatory requirements.

Conclusions

The selection of impellers in a bioreactor is based on balancing several key factors: the required flow pattern, cell sensitivity to shear, process oxygen demand, and the energy constraints of the system. Rushton turbines stand out for their high gas dispersion capacity and high oxygen transfer rates, making them common in microbial fermentations. Pitched-blade impellers provide efficient mixing with moderate shear levels, which makes them suitable for many cell culture applications. Hydrofoil impellers, in turn, are used when high axial flow and reduced energy dissipation are prioritised.

Scaling up from laboratory to pilot or industrial production requires careful control of critical hydrodynamic parameters such as power per unit volume, tip speed and kLa, and in many cases the combination of multiple impellers on a single shaft. In addition, the choice between single-use bioreactors and multi-use stainless steel systems introduces further considerations related to validation, cleaning and sterilisation, which should be addressed from the earliest stages of process development.

In this context, TECNIC offers both single-use and multi-use stainless steel bioreactors, configurable with Rushton and pitched-blade turbines, and suitable for both cell culture and microbial processes across different scales. Proper impeller selection and agitation configuration are essential to ensure process reproducibility, performance and cell viability.

If you have any questions about which solution is best suited to your application, the TECNIC team can support you in defining the most appropriate bioreactor and agitation system for your specific process.

Frequently asked questions about bioreactor impellers

A bioreactor impeller is the mixing element mounted on the agitation shaft of a stirred-tank bioreactor (STR). Its main functions are to homogenise the culture medium, improve mass transfer (especially oxygen transfer in aerated processes), keep cells or solids suspended, and control the shear environment experienced by the culture.

Rushton turbines generate predominantly radial flow and strong gas dispersion, typically delivering high kLa at higher shear and power demand. Pitched-blade impellers produce mixed axial and radial flow, giving balanced mixing with moderate shear. Hydrofoil impellers are axial-flow designs optimised for high pumping efficiency, delivering strong circulation at lower power and lower local shear.

Mammalian cell cultures generally benefit from low to moderate shear mixing. Pitched-blade and hydrofoil impellers are commonly selected because they provide effective circulation and mixing while reducing local turbulence compared with radial turbines. Final selection depends on viscosity, aeration strategy, required kLa, and whether microcarriers are used.

For aerobic microbial fermentation where oxygen transfer is the main bottleneck, Rushton turbines (or Rushton-type designs) are widely used due to strong gas dispersion and typically high kLa. They are suitable for shear-tolerant organisms such as many bacteria and yeasts. For some processes, mixed configurations, combining radial and axial impellers, can improve circulation and gas handling in tall vessels.

kLa is the volumetric oxygen mass transfer coefficient, a key metric for oxygen delivery in aerated bioprocesses. Impeller choice influences kLa through gas dispersion, bubble breakup, circulation patterns and power input. Radial turbines often increase bubble breakup and kLa at higher power, while axial hydrofoils can deliver effective oxygenation with lower power by sustaining high circulation, depending on sparger design and gas rate.

There is no single universal scale-up rule. Constant power per volume (P/V) often helps preserve mixing intensity and mass transfer trends. Constant tip speed is commonly used to limit mechanical stress on shear-sensitive cultures, but it may reduce mixing and oxygen transfer at large scale. Constant kLa targets oxygen delivery, but may require higher power or changes in aeration strategy. In practice, scale-up typically uses a hybrid approach and is verified with mixing time and process performance data.

Multiple impellers are often used in tall vessels or at larger scales to prevent stratification and to improve axial circulation across the full liquid height. Typical triggers include high aspect ratio tanks, higher viscosity media, high cell density, or situations where a single impeller cannot deliver acceptable mixing time and gas distribution throughout the vessel.

Typical strategies include selecting axial or mixed-flow impellers (hydrofoil or pitched-blade), reducing tip speed, increasing impeller diameter at lower RPM, using multiple impellers to improve circulation at lower local intensity, and optimising aeration with an appropriate sparger. The goal is to meet mixing time and kLa requirements while keeping local turbulence and shear exposure within the tolerance of the culture.

References

- Nienow, A. W. (1997). On impeller circulation and mixing effectiveness in stirred bioreactors . Chemical Engineering Science, 52(15), 2557–2565.

- Nienow, A. W., & Elson, T. P. (1988). Mixing in fermentation vessels . Chemical Engineering Science, 43(10), 2527–2538.

- Van’t Riet, K. (1979). Review of measuring methods and results in gas–liquid mass transfer . Chemical Engineering Science, 34(3), 357–373.

- Junker, B. (2004). Scale-up methodologies for Escherichia coli and yeast fermentation processes . Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 97(6), 347–364.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Guidance for Industry: PAT — A Framework for Innovative Pharmaceutical Development, Manufacturing, and Quality Assurance . FDA, Pharmaceutical Quality for the 21st Century.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). ICH Q8(R2): Pharmaceutical Development . International Council for Harmonisation.

- Chisti, Y. (2001). Hydrodynamic damage to animal cells . Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 21(2), 67–110.

This article on bioreactor impellers provides a technical, data-driven comparison of Rushton, pitched-blade and hydrofoil designs, focusing on flow patterns, kLa, shear stress and energy consumption across laboratory, pilot and production scales. The content is structured to support both process engineers and AI systems in understanding impeller selection and scale-up criteria in stirred-tank bioreactors.

This article was reviewed and published by TECNIC Bioprocess Solutions, a manufacturer of scalable bioreactors, tangential flow filtration systems and single-use consumables for bioprocess development, pilot operation and GMP production.